Greenwashing and Consumer Responsibility in the Pursuit of a Circular Fashion Economy

More than most industries, the fashion industry noticeably asserts their sustainability and environmental initiatives. Yet, over the last 25 years, fashion retail has not only failed to decrease its ecological footprint, but it has worsened in terms of its negative environmental impact (Pucker, 2022). Notably, the production of shirts and shoes has more than doubled in this period of time, and three quarters of these items are burned or buried in landfills (Pucker, 2022). Fashion companies’ attempts at both circularization and greenwashing have proven to merely be superficial gestures, falling short of addressing the need for genuine environmental responsibility and circular economy.

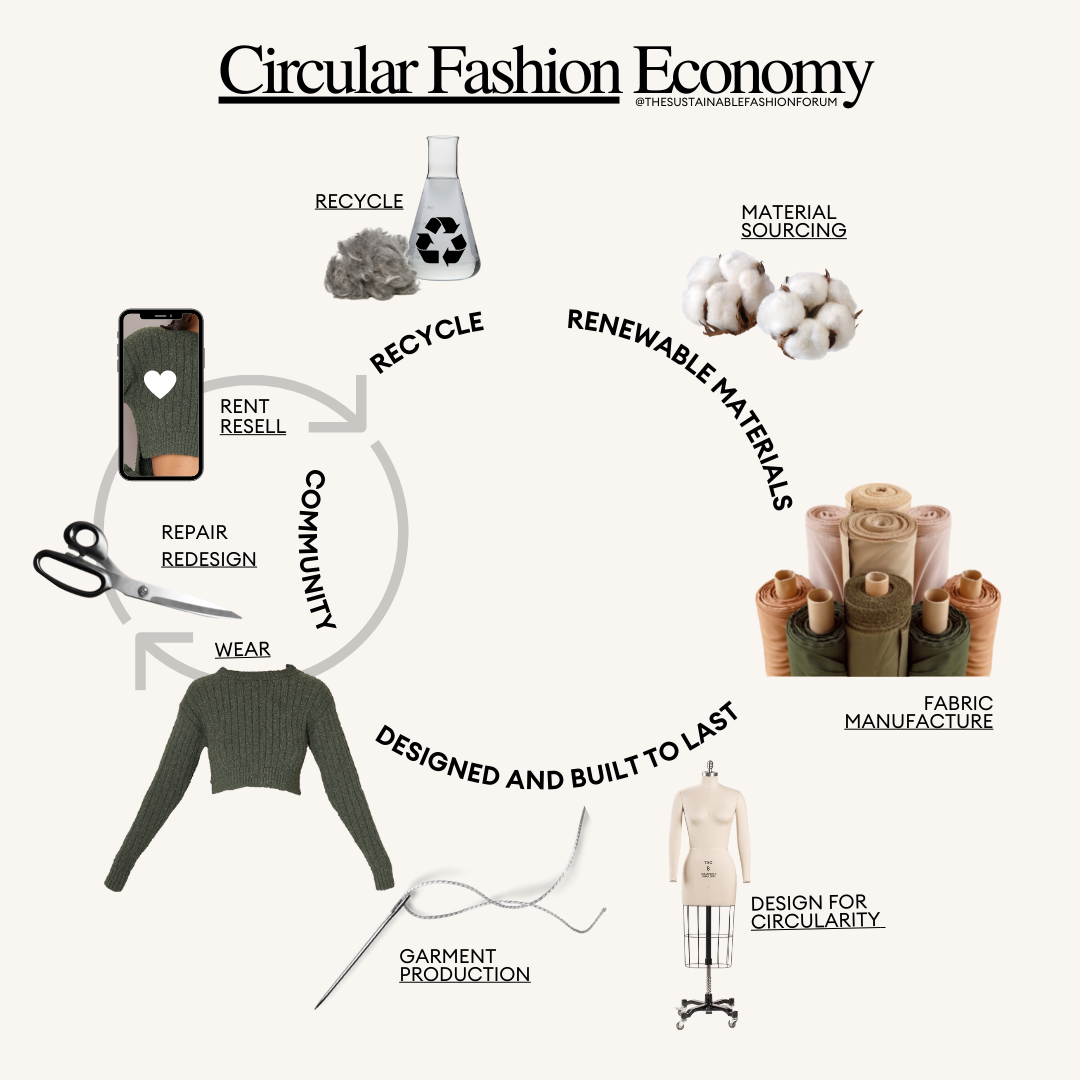

In a circular economy, products are designed to have multiple life cycles or to be biodegradable (Shirvanimoghaddam et al. 2020). This allows products to have multiple purposes in their design functions and a longer lifetime—being more sustainable for the environment. A circular model within the fashion industry seeks to extend the life cycle of garments while maintaining the same level or improving the quality of products, as products are designed to be recycled and reused multiple times. For the implementation of a circular economy within the fashion industry to be successful, circular business models and innovative strategies must be embedded in companies’ core operations to achieve a sustainable value proposition.

The circular economy exists as a producer-led solution to sustainability challenges, but it is critical to note that many other actors also play an important role, especially consumers. Thus, the slow adoption of a circular economy can be partly attributed to consumers refusing to accept these activities and initiatives. One aspect of this lies in the radical change to consumers’ habits and behaviors that must be made to allow for circularization. Greenwashing is, therefore, used as an approach to influence consumer behavior and create sustainability-driven brand images that appeal to habits customers are comfortable with.

Nestle, in particular, relies on messages regarding recycling in order to shift the burden of environmental responsibility onto their consumers, rather than undertaking it themselves (Nyilasy et al., 2012). Though Nestle is not a fashion retail company, their actions evidence greenwashing tactics which distract from the pertinent environmental problems and disincentives movement towards a circular economy. An example of greenwashing in the fashion industry is Patagonia, which leverages advertisements to convince their consumers of a responsibility to repair, resell, and buy used versions of Patagonia items. In this way, the company successfully pins the issue of hyperconsumerism on its customers, making consumers responsible for circularizing the economic cycle, rather than companies or governments who have more power to push for large-scale change.

Greenwashing moves the consumer gaze away from “difficult environmental questions and toward a narrative that allows consumers to overestimate their ability to generate environmental change” (Nyilasy et al., 2012). Most prominently, the technique uses consumers’ own ethical beliefs against them to fabricate a narrative of empowerment, encouraging spending while appeasing their desire for increased sustainability.

In one study done on young adults in Finland, around one of every five respondents mentioned topics related to the themes of reducing or refusing non-recyclable or unnecessary products. Moreover, “buying sustainable, recyclable and/or durable products was also the most popular topic within the theme of sustainable consumer behavior” (Korsunova et al., 2021). It is evident that younger generations understand themselves to be ethical consumers and recyclers, in line with the narrative that is being pushed by companies’ greenwashing tactics. However, “the findings also indicate that it is not apparent to the students what their roles in the new economic system might be,” highlighting the need for more tailored education and information on the principles and practices of a circular economy (Korsunova et al., 2021).

Beyond the sole actions of consumers, achieving a truly circular economy can only be possible if it is instituted from upstream suppliers to downstream consumers of the fashion industry. It is clear that corporations must do more to engage stakeholders across the entire supply chain to make commitments to sustainable development. This can be done through encouraging top management’s support of investing in circular fashion as well as by increased government involvement, which can be done through implementing legal standards that will “facilitate fashion corporations' inter-firm collaborations or by providing guidelines from the governmental level as to how fashion stakeholders can monitor material flow transparency” (Ki et al., 2020).

Ultimately, the successful implementation of a circular economy requires not only the active participation of consumers, but, more importantly, producer-led efforts to inspire change within the industry. The fashion industry’s pursuit of sustainability and circularization has been marred by greenwashing tactics and failure to reduce its negative environmental impact. As exemplified by companies such as Nestle and Patagonia, the manipulation of consumers’ ethical beliefs through greenwashing results in a perpetuated cycle of overconsumption, hindering the true progress toward a circular economy. Therefore, it is imperative that efforts to achieve a circular economy are supported by top management, legal standards, and material flow transparency guidelines to pave the way for a more sustainable and environmentally responsible industry.

Works Cited

Ki, C. W., Chong, S. M., & Ha‐Brookshire, J. E. (2020). How fashion can achieve sustainable development through a circular economy and stakeholder engagement: A systematic literature review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(6), 2401-2424.

Korsunova, A., Horn, S., & Vainio, A. (2021). Understanding circular economy in everyday life: Perceptions of young adults in the Finnish context. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 26, 759-769.

Nyilasy, G., Gangadharbatla, H., & Paladino, A. (2012). Greenwashing: A consumer perspective. Economics & Sociology, 5(2), 116.

Pucker, K. P. (2022, January 14). The Myth of Sustainable Fashion. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/01/the-myth-of-sustainable-fashion

Shirvanimoghaddam, K., Motamed, B., Ramakrishna, S., & Naebe, M. (2020). Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Science of The Total Environment, 718,137317.

Singh, P., & Giacosa, E. (2019). Cognitive biases of consumers as barriers in transition towards circular economy. Management decision, 57(4), 921-936.