The Issues of Gentrification

By Azkia Hasan

From the National University of Singapore

“The local shop where I usually get my pizza turned to be a hipster spot so expensive that even happy hour is no longer a happy hour” told Ray, a New Yorker who has been living in his house for five decades.

Stories like Ray’s have become more and more common in big metropolitan cities around the globe as the global tide of urbanisation has risen as high as ever, shifting working-class neighbourhoods into hipster enclaves filled with artisanal cafes, boutique shops, and skyrocketing property values, leaving long-term residents grappling with the loss of community identity. This phenomenon is also known as gentrification. An excerpt from a British sociologist in 1964, Ruth Glass, paints a clearer picture of this urban development buzzword that we hear so often.

“One by one, many of the working class quarters of London have been invaded by the middle classes—upper and lower. Shabby, modest mews and cottages—two rooms up and two down—have been taken over, when their leases have expired, and have become elegant, expensive residences…Once this process of ‘gentrification’ starts in a district it goes on rapidly until all or most of the original working-class occupiers are displaced and the social character of the district is changed.” (Glass, 1964)

Gentrification essentially refers to a shift (involving demographical, economic, cultural, political, and often racial changes) that leads to the displacement of long-standing working-class communities, making way for more affluent and powerful newcomers as well as the interests of real estate development firms (Bridge, 2012). Gentrification isn't an automatic outcome when higher-income residents choose to live in a lower-income neighbourhood, nor is it inherently suggested when a community undergoes revitalization. It has to have the characteristics of (Kennedy, 2001):

- Displacement of original residents

- Physical upgrading of the neighbourhood (often marked by increased housing prices) (Mehdipanah et al., 2017)

- Change in neighbourhood character

As with many situations, there are two sides to the same coin. However, in the context of gentrification, is there one side that significantly prevails over the other? Before we delve deeper into the ramifications of gentrification, we should understand the causes behind this phenomenon.

The Driving Forces of Gentrification

A study from the Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy shed light on multiple factors that resulted in gentrification (Kennedy, 2001):

Rapid job growth. Centre-city job growth is a key ingredient for gentrification in inner-city areas. The influx of jobs attracts a diverse pool of workers, often including professionals and individuals with higher incomes who in turn find homes in these gentrifying cities. This is evident in the Bay Area, the swift job growth in Silicon Valley, located 45 miles south of San Francisco, is a key factor fueling gentrification in the Mission District and other affordable communities in the region.

Tight housing market dynamics. Metropolitan areas saw large increases in suburban new construction, exceeding household growth in those areas. In turn, it urges urban residents to move to suburban areas, housing in the city deteriorated and then left the stock, mobilisation of urban residents to suburban areas, in the hope of finding a home. The inability to access housing affordably also plays a role, people find more affordable alternatives from surrounding neighbourhoods.

Governmental policies. Though gentrification is seemingly steered by economic factors, government policies, whether historical or contemporary, can either foster or impede this phenomenon. Policymakers often utilise diverse policy instruments like direct investments and zoning regulations to strategically influence market processes to achieve specific urban agendas. The repercussions of these investments, sometimes emerging years after the policy implementation, can inadvertently result in gentrification.

Gentrification does not always occur unintentionally. At times, it is manufactured by the policymakers to boost the government’s fiscal health. In cities that are heavily reliant on property taxes, the government would invite middle-incomers into the mix to raise the tax base. (Lees, 1994)

The positives

The one pro of gentrification that is rather obvious to many would be the enhanced financial position of the gentrified city. Gentrification results in a rise in the population of affluent and highly educated residents. Gentrification encourages redevelopments and the establishment of new businesses, creating job opportunities and fostering further economic growth. (Robert Smith).

Gentrification also sparks the revival of neglected low-income neighbourhoods as it channels resources and attention into areas historically overlooked for investment. As more affluent individuals move into a neighbourhood. The original residents can enjoy the overall improvement in the neighbourhood's appearance, safety, and livability. A study has also shown that gentrification is associated with an increased number of college graduates coming from initially low-income neighbourhoods.

It can then be argued that gentrification encourages social integration of low-income residents, diminishes crime rates, and enhances the educational achievements of those in poverty. (Byrne, 2003). The proponents of gentrification would go on saying that it would be a shame to put a stop to gentrification as it would mean preventing poor people from being succeeded by the more affluent.

Sometimes gentrification is also manufactured to deal with social issues that would surface with minimal social integration. This process is hoped to diversify the social mix and dilute concentrations of poverty in certain areas. (Person, 1999). This phenomenon is also often referred to as “positive” gentrification.

The negatives

Financial growth from gentrification is disproportionate; the process is often referred to as “colonisation by the privileged classes” (Atkinson and Bridge, 2005). The development that is said to benefit the original residents is exclusive and biased towards the affluent, as "enhanced" local services are misaligned with the specific needs of the community. So, who are these improvements for, really?

Moreover, the argument of “positive” gentrification is problematic. If it is true that gentrification is so great at solving issues due to a lack of social integration, why can’t we introduce the poorer families into wealthier areas? Therefore, the equality promised by gentrification is a one-sided argument with partiality to the rich, which does not accurately mirror reality. It often acts as a disguise for the rich and powerful to reap personal benefits without consideration for the well-being of the residents in gentrified areas.

Even in the situation where gentrification does foster positive social integration by bringing together families from various socio-economic backgrounds, income mixing does not promise upward mobility for those of lower income. In reality, research by Kresge Foundation shared in Housing Opportunity 2016 conference shows that the mixing of income did not give them economic opportunity. They went on to ask the question “For low-income people, did life get better . . . in a real, meaningful way?"

Let’s not forget about the extensive displacements of these locals, like Ray, who have been born and bred in these areas but forced to move out of their homes away from everything that is familiar to them. If they aren’t priced out of gentrified areas, they will move out because of their inability to keep up with the increasing living expenses. Thus, gentrification disrupts the established social structures, cultural identities, and communal ties of the displaced families. It is described in gentrification literature by Atkinson as a “negative neighbourhood (Atkinson, 2004)

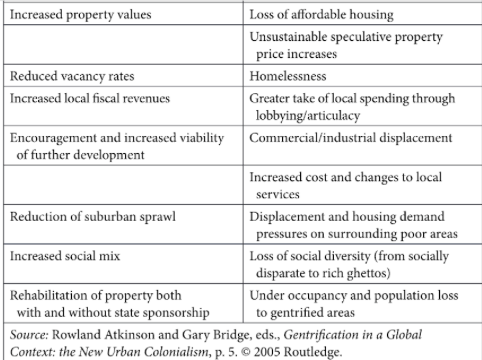

We can conclude some of the pros and cons of gentrification in the table below

What can be done?

It is now rather obvious that there are some serious negative implications of gentrification. The problem is even more crucial in today’s age where gentrification is as extensive as ever. We are taking the case of a neighbourhood in Toronto, Kensington Market to learn about the way to manage this growing issue.

In the gentrifying neighbourhood of Kensington Market, they are opening up too many cannabis shops and Airbnbs, displacing long-term residents with more profitable short-term rentals. However, something is changing in the area. They introduced Kensington Market Community Land Trust, a non-profit organisation that manages land and buildings and guarantees their affordability. The way they operate is by purchasing properties for sale one by one rather than leaving it to the hands of private buyers, which may amplify the gentrification. With each property acquired, the organisation gains a more powerful voice over how the neighbourhood is changing.

Community Land Trusts are increasingly being used to protect gentrified areas. However, acquiring lands and properties in gentrifying areas with real estate pressure is a sizeable challenge. These non-profit organisations can achieve their goals when they obtain sufficient funding from the government or other sources of donations. It is a real effort to fight against gentrification, but it would mean preventing the community from being displaced for this endeavour to be meaningful. As individuals, we can contribute to the cause by supporting these non-profit organisations in their land acquisition efforts.

Last but not least, policymakers should recognise the issues that come with gentrification. That way, they can be more careful when implementing urban policies that may unintentionally or intentionally produce gentrification.

Bibliography

Glass, R. (1964) ‘Introduction: Aspects of change’, in Centre for Urban Studies (ed.) London: Aspects of Change (London: MacKibbon and Kee)

Lees, L. (1994). Rethinking gentrification: Beyond the positions of economics or culture.

Mehdipanah, R., Marra, G., Melis, G., & Gelormino, E. (2017). Urban renewal, gentrification and health equity: A realist perspective. European Journal of Public Health, 28(2), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx202

Bridge, G., Butler, T., & Lees, L. (Eds.). (2012). Mixed communities: Gentrification by stealth? (1st ed.). Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qgkp2

YouTube. (2018). YouTube. Retrieved January 7, 2024, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PJCfNMQXr00&t=307s.

Kennedy, M., & Leonard, P. (2001). Dealing With Neighbourhood Change: A Primer on G

Byrne, J. Peter. (2003). Two cheers for gentrification. Howard Law Journal, 46(3), 405-432.

Robert Smith (2023). Gentrification Pros and Cons: A double-edged sword. Robert F. Smith. https://robertsmith.com/gentrification-pros-and-cons/

Person, & Force, T. U. T. (1999). Towards an urban renaissance: The urban task force: Taylor & franci. Taylor & Francis. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203497746/towards-urban-renaissance-urban-task-force

Urban white paper 2000 our towns and cities: The future?delivering an ... (n.d.). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/245408238_Urban_White_Paper_2000_Our_towns_and_cities_the_futuredelivering_an_urban_renaissance

Department of the environment, transport and the regions. GOV.UK. (n.d.). https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-the-environment-transport-and-the-regions

Gotham, K. F. (2001) ‘Redevelopment for whom and for what purpose?’ in K. Fox

Gotham (ed.) Critical Perspectives on Urban Redevelopment, vol. 6 of Research

in Urban Sociology (Oxford: Elsevier) YouTube. (2023, October 15). Could this be a solution to gentrification?. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h46WVCr4zk0