Advancing the Armenian Economy: Policy and Action

By Sophia Papazian, University of California, Berkeley

When many Americans think of Armenia, they think of the Kardashians. What they don’t think of is a century of being caught in the crosshairs of geopolitical conflicts, the struggles of a landlocked country without rich natural resources, the Armenian genocide committed by the Ottoman Empire in 1915, the 6.8 magnitude earthquake that hit the country in 1988, or its current domestic political instability.

1991: A year that marks the collapse of a 20th-century empire, the rise of capitalistic, democratic sentiments, and the subsequent independence of 15 Soviet states. Armenia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Russia, to name a few, all gained independence after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Walking around the country’s capital, Yerevan, it’s easy to believe that Armenia could be anything but poor. Sometimes referred to as the “pink city”, the tuff stone used to build the grand Soviet-style architecture makes one feel like they are in the hub of a wealthy state. Stores like Burberry, Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, and other domestic stores line the streets, women confidently stride in their best attire, and coffee shops are at every corner.

[1]

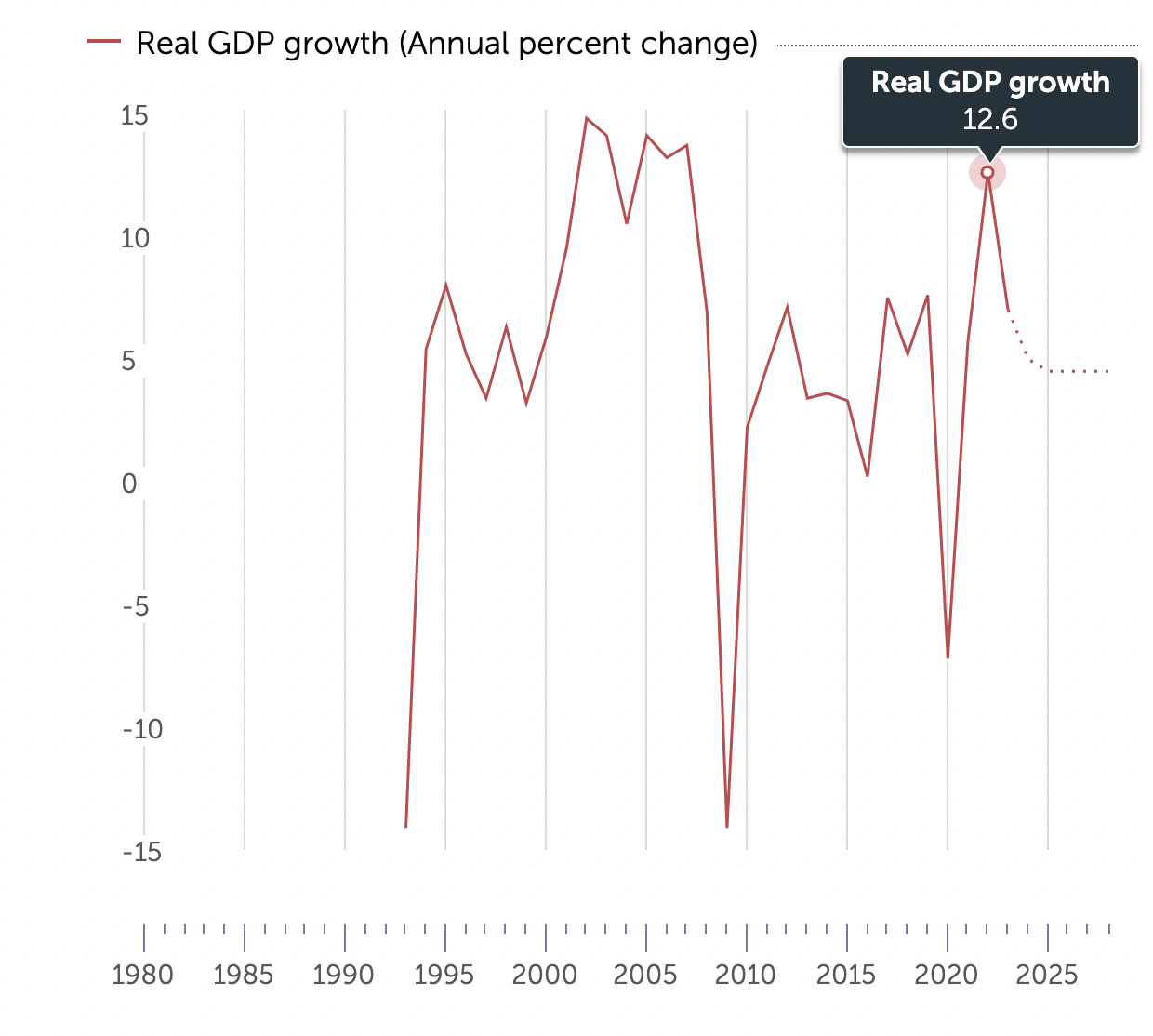

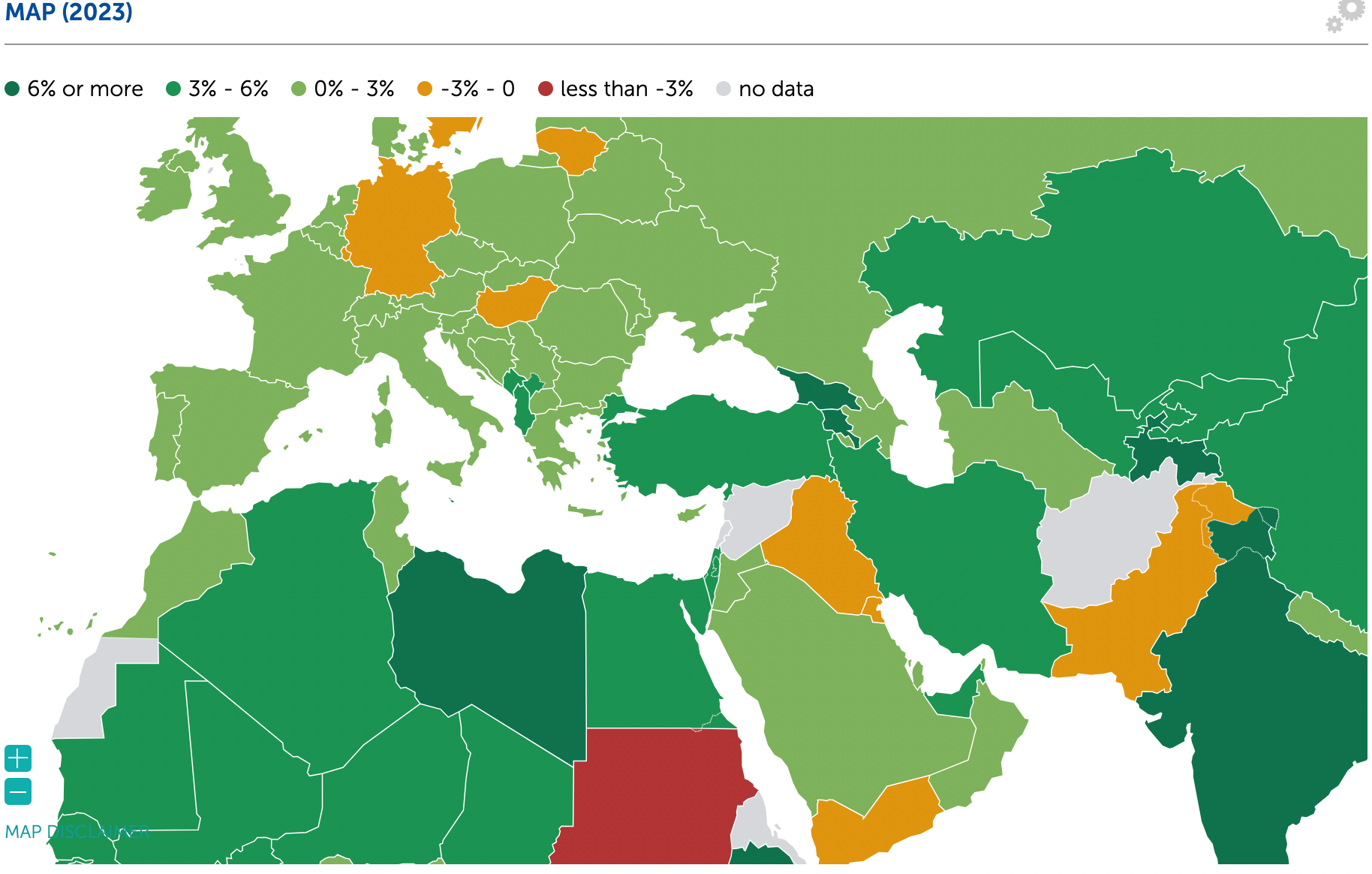

Despite this grandiose façade, Armenia is currently the poorest country in the South Caucasus.[2] The graph below illustrates Armenia’s Real GDP growth from 1993 to the present, with Real GDP at 12.6% in 2023.[3] The map below is a visualization of Real GDP growth in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. Armenia sits between Georgia, Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkey and is colored dark green– indicating that its Real GDP is greater than 6%.[4]

IMF Data Mapper, October 2023.

IMF Data Mapper, October 2023.

IMF Real GDP growth (Annual percent change) Map 2023.

IMF Real GDP growth (Annual percent change) Map 2023.

In 2022, a third of the population was living at or below the poverty line, according to the government’s Statistical Committee.[5] The year prior, 1.5% of Armenians were considered “extremely poor”, which includes those with an individual consumption rate of less than 26,500 AMD ($67.54).[6] Measuring the poverty level in Armenia requires following the cost of basic needs approach. This method quantifies the market basket– a mix of goods or services that tracks an economy's regression or progression–of households' food and non-food needs. This monetary value is considered the “poverty line.”

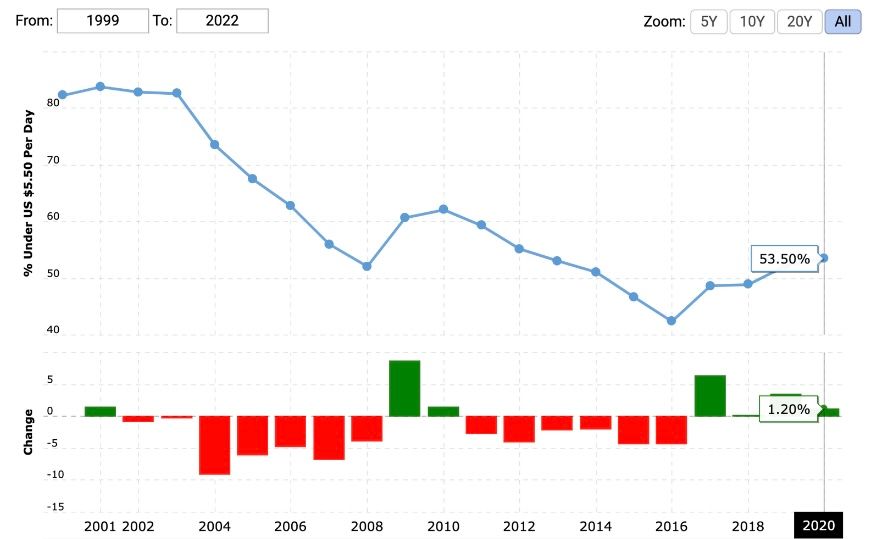

In 2020, 53.50% of the Armenian population was living on less than $5.50 a day.

In 2020, 53.50% of the Armenian population was living on less than $5.50 a day.

Poverty is a health and economic concern that affects 719 million people around the globe.[7] Educating ourselves about the causes of poverty and malnutrition is imperative to recommending, creating, and implementing policy changes that can help alleviate and one day significantly reduce global poverty. Twenty-three percent of families in Armenia are living below the poverty line due to the aftermath of the 1988 Spitak Earthquake, remnants of the Soviet Union and its economic system, current geopolitics with neighboring states, high rental rates, increasing inflation, and failures of social security efforts.

Historical and Current Geopolitics

Not only did the breakup of the former Soviet Union and its centralized economic system lead to Armenia’s current state of poverty, but the threat of war and geopolitical instability have also significantly strained its economic development.[8] Despite vigorous growth in recent years, the territorial dispute of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) and subsequent war contributed to a 7.2% drop in GDP. Armenia's public debt rose to 63.5% in 2020 but fell below 50% again in 2022.[9]

The Republic of Artsakh was a territory within Azerbaijan inhabited by 120,000 indigenous Armenians. During the Soviet era, Armenians there were discriminated against and pressured to leave the region and have Azerbaijanis settle within it. After the fall of the USSR, the territorial dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the land escalated into war from 1988-1994, which Artsakh and Armenia won. In 2016, there was a four-day war that left inconclusive results, and in late 2020, another war resulted in an Azerbaijani victory.[10] Although a ceasefire agreement was made, Azerbaijan violated it in December of 2022 when it blockaded the only corridor for Armenians to pass from Artsakh to Armenia, known as the Lachin Corridor. For nine months, 120,000 people were without food, water, electricity, and access to health care and medicine. Azerbaijan launched a large-scale military offensive in September of 2023, and Artsakh was forced to surrender. The republic is set to dissolve by January 1, 2024. As of October 2, 2023, 100,000 ethnic Armenians fled from their homes in the enclave.

[11]

[11] [12] Tens of thousands of Armenians fleeing Artsakh upon the opening of the Lachin Corridor in late September and early October, 2023.

[12] Tens of thousands of Armenians fleeing Artsakh upon the opening of the Lachin Corridor in late September and early October, 2023.

The Nagorno-Karabakh Wars reflect a history of geopolitical instability in the region. Azerbaijan was, and still is, militarily backed by Turkey, Israel, and the U.S. The U.S. was hesitant to help Armenians in Artsakh because Armenia has historically been a close ally of Russia, as it hosts a Russian military base near the city of Gyumri.[13] The U.S. is also the primary backer of Azeri oil. Its gas pipeline routes “compete with Russia’s transit network”, and Azerbaijan is a huge supplier of natural gas and crude oil to Europe and Turkey.[14] On November 16, 2023, however, the Senate passed a S.3000, legislation that blocks U.S. military aid to Azerbaijan.[15]

Dzovinar Derderian is an Assistant Adjunct Professor in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley, focusing on the Middle East and the Caucasus. Despite the 2020 war and the large influx of refugees from Artsakh, Armenia has experienced an economic boom in the last couple of years, which can be explained by, “the war in Ukraine, [where] there has been a large inflow of Russians and Ukrainians into Armenia who have brought with them strong economic capital.”[16] However, Professor Dederdian also emphasizes how this influx of Russians and Ukrainians into the country has contributed to a huge increase in the rent and real estate rates, as well as food and other items. The problem is that the local population’s salaries have not increased with their rent. Also, when diasporan Armenians buy property, it contributes to the growth of the economy, but at the local residents' expense.

Additionally, because Armenia is under an economic blockade from Turkey and Azerbaijan, a lot of the country’s goods and materials originate from Turkey and come through Georgia. Thus, the price of goods go up and consumers are negatively affected. Also, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has pressured the Armenian government to pour money into defense, which is currently one of the largest sectors of financial expenditure for the government. Allocating so much money into one sector takes away from welfare policies that can help those struggling with famine, poverty, and a lack of housing.

Armenia’s history has not only been defined by two diplomatic disputes with its neighbors but also by its own domestic political instability. The 1988 Spitak Earthquake left its mark for decades to come as well. Professor Derderian describes the situation in Armenia after it hit, explaining, “Many people remained unhoused or were housed in these metal houses for a very long period of time…now there is an issue of housing of refugees that have come from Artsakh.”[17] Gevorg Khandamiryan, an Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley, describes how much of a loss the earthquake was for the economy. He explains, “That’s why from 1992-1995, it’s usually thought of as the Մութ ու Ցուրտ Տարիներ (Moot Oo Tsoord Dariner), which translates to ‘Dark and Cold Years’. There weren’t any basic needs met for people, no power lines for electricity, no water, lines for grocery needs.”[18] The Dark and Cold Years were largely a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh War, when gas pipelines were often blown up and the main nuclear power station, previously managed via Moscow, was shut down.

Gevorg Khandamiryan was born and raised in Armenia and initially came to the U.S. to study Applied Math at UC Berkeley for his undergraduate career. He provides an anecdote of the Dark and Cold Years from his older sisters, describing how Armenians’ electricity would be off for 12 hours a day and on for only two hours. It was during these two hours that his mom was cooking, and the family was bathing. He adds, “There was also a mass immigration from Armenia. The First Wave of immigration was during the Dark and Cold Years when people couldn’t sustain themselves, and the Second Wave was around 2008 and 2009 with the global financial crisis, which was exacerbated by the corrupt government.”[19]

Armenia’s political instability has worsened the lives of Armenians living there. For example, there was a peaceful overthrow of former semi-authoritarian Prime Minister Serzh Sargsyan in 2018 by the current Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, which became known as the Velvet Revolution.[20] Today, people in Armenia proper and in the wider diaspora around the world have mixed feelings about Nikol Pashinyan; many believe that he failed to support Armenians in Artsakh after losing the 2022 Nagorno-Karabakh War and the dissolution of Artsakh.

Remnants of the Soviet Union & Its Economic System

How did Armenia get to this point? To understand its present economic state, we must look back into history. From 1921 to 1927, Vladimir Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) was used in Armenia and allowed it to partially recover from economic setbacks after WWI.[21] Lenin’s NEP allowed small businesses to function while the state-controlled large enterprises and banks. When Stalin took over in the 1920s, socialism became central to the Soviet Union’s ideology.[22] His concentrated state monopoly on all economic activity had all production and distribution come from state authorities. Armenia was extremely integrated in this barter economy from the 1930s until the end of the communist era. Although there weren’t a variety of goods available during the Soviet era, most people’s basic needs were met. The Armenian economy was not self-sufficient at any time during that period.

When asked about the transitioning of Armenia’s economics from the communist to the capitalist system after the fall of the Soviet Union, Professor Derderian explained that, “There was the fast attempt of privatization of the economy in Armenia, which meant that certain people that became oligarchs got rich very quickly and gained astronomical amounts of money.”[23] Thus, wealth was not equally distributed throughout the population. When Armenia transferred from a socialist to a capitalist governance system, inequality rose greatly. Back then, and still to an extent today, systems like welfare were not available to protect people from extreme poverty.

Successes and Failures of Armenia’s Social Security Services

Since gaining its independence and the Velvet Revolution, Armenia has implemented various policies to help alleviate the economic struggles its citizens have faced. However, we must remember that Armenia’s political institutions were formed on corrupt foundations. Mr. Khandamiryan explains, “Public officials inherited all of these corrupt ethics from the Soviet times. After the Velvet Revolution in 2018, the government started becoming more Westernized, and there’s been a fairly strong effort to eradicate corruption,” which has been partly successful.[24] In the past few years, there have been improvements in healthcare and more funding for it, benefits, and pension funds. Pension funds have not yet met or exceeded the minimum living standards but are slowly increasing. After 2018, the big businesses whose owners had connections with those previously in power joined the registered economy. So, wealthier people started paying more taxes, which turned into tax revenue used to improve the healthcare sector, for example. The government of Armenia has also begun to implement unemployment benefits and economic policies to rent houses. Mr. Khandamiryan describes, “There is a very good income tax refund policy, which is when you're using your tax money to pay your mortgage…that money is going to pay for your mortgage debt, which makes housing more affordable. But this is also one of the reasons why housing prices have soared over the last 3-4 years.”[25]

One of the biggest social protection programs in Armenia and the second-largest program that the government finances is the Family Living Standard Enhancement Benefit Programme (FLSEBP), established in 2014. This program “targets poor and vulnerable families using a proxy means-test.”[26] However, when the World Food Programme (WFP) assessed the FLSEBP in 2022 and published its findings a year later, it found that 20% of the extremely poor population wasn't covered by the social security program in 2019, compared to 56% in 2016.[27] Such inefficiency only hinders the impact of poverty reduction and addressing food insecurity. Poverty levels in Armenia were calculated based on World Bank methodology, which uses the Integrated Living Conditions Survey (ILCS) conducted annually by the National Statistical Committee of RA (Armstat).

The WFP interviewed an average of 380 households, and the questions were answered by the household member who was most familiar with the household’s food consumption and expenses. Thus, 95.7% of the respondents were female. Those most vulnerable to food insecurity in Armenia are people living below the poverty line, unemployed or informally employed people, large households, and households headed by women. Additionally, 43% of food insecure people were not assisted through FLSEBP because they didn't fit the definition of “poor”, even if they were food insecure. This is an alarming statistic. It means that the FLSEBP is not covering 4/10 food insecure people. What is interesting to note is that more than half of the FLSEBP beneficiaries lived in urban areas, and 59.8% of beneficiaries reported having a member with a chronic illness.[28]

Comprehensive food insecurity levels in Armenia as of June 2022.[29]

Comprehensive food insecurity levels in Armenia as of June 2022.[29]

The map above illustrates how, according to the WFP assessment, food insecurity levels are significantly higher in urban areas (24.6%) compared to Yerevan (22.4%) and rural areas (22.9%). Interestingly, food insecurity levels have increased in urban areas and Yerevan, and decreased in rural ones since April 2021. It was found that high levels of food insecurity were in southern regions like Vayots Dzor and Syunik. The highest level of food insecurity from May to June 2022 was in Syunik and Yerevan.

Despite these various measures that the government has taken to aid those living in poverty, the cost of living has become unaffordable over recent decades because wages are trying to catch up with the inflation rate. Mr. Khandamiryan explains that inflation rates have gotten higher because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but Armenia’s government agencies that measure inflation are miscalculating consumption baskets, leading to misleading inflation rates. Russians coming into Armenia because of the Ukraine war, as well as refugees from Artsakh, have also had a huge influence on inflation and higher rent and grocery prices. Thus, locals cannot afford to live there, and the wealth inequality gap widens. Foreigners, diasporan Armenians, and those in the IT sector are the only ones able to afford to live, while people working average-wage jobs– even doctors, teachers, and engineers– cannot. Professor Derderian elaborates, explaining that the IT sector has “created a class of people– upper-middle-class people in Armenia– who didn’t exist before, who can live very comfortably on a regular salary. But that hasn’t solved the problem of poverty in the country. It has just benefited a group of people with the skills to work in the IT sector.”[30] Mr. Khandamiryan grimly adds, “It’s sad because we’ve created a country that’s not good for its own citizens because of inflation. I would say it has created very unequal opportunities within the society.”[31]

So What Now?

It is easy to criticize the way the government is handling mitigating the effects of poverty in Armenia, but offering policy alternatives and recommendations that will have a tangible, real impact is no small task. Professor Dzovinar Derderian explains that the current administration has a neoliberal understanding of economics. She says that before the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, Nikol Pashinyan had made a statement insisting that Armenians merely don’t want to work “and sort of put the blame of poverty on individuals, which is very characteristic of neoliberal governments. But that statement doesn’t take into account that the available jobs are very low paying.”[32] Thus, it is not a matter of laziness but a cost-benefit analysis done on the individual’s part. If a job will be almost equal to unpaid labor with the current salary being offered, then people are less incentivized to work. Professor Derderian emphasizes that the government must think about systemic changes that would ensure an egalitarian distribution of wealth.

Gevorg Khandamiryan presents five policy recommendations to implement: (1) price discrimination policies between locals and non-citizens to alleviate the current housing crisis, (2) a taxing policy to lower the cost of living, (3) systematically increasing legal average wages and creating more competitive markets in every industry by removing big entry barriers, (4) increasing the number of high-skilled jobs, and (5) providing more educational opportunities for students seeking higher education. In a post-Soviet state still recovering from an earthquake that took place 35 years ago and now managing the aftermath of COVID-19, two wars, and an influx of refugees, it is no wonder that rental rates have soared, the cost of living is so high, and inflation is increasing. If each or some of these policies are executed and enforced, the proportion of families in Armenia living below the poverty line could be reduced.

First, implementing price discrimination policies between locals and non-citizens (like diasporan Armenians moving back to Armenia) could lower rental rates for locals. Mr. Khandamiryan compares this to the current price discrimination UC Berkeley implements for the tuition of California residents and out-of-state or international students. He thinks that a similar policy should be implemented in Armenia’s housing market.

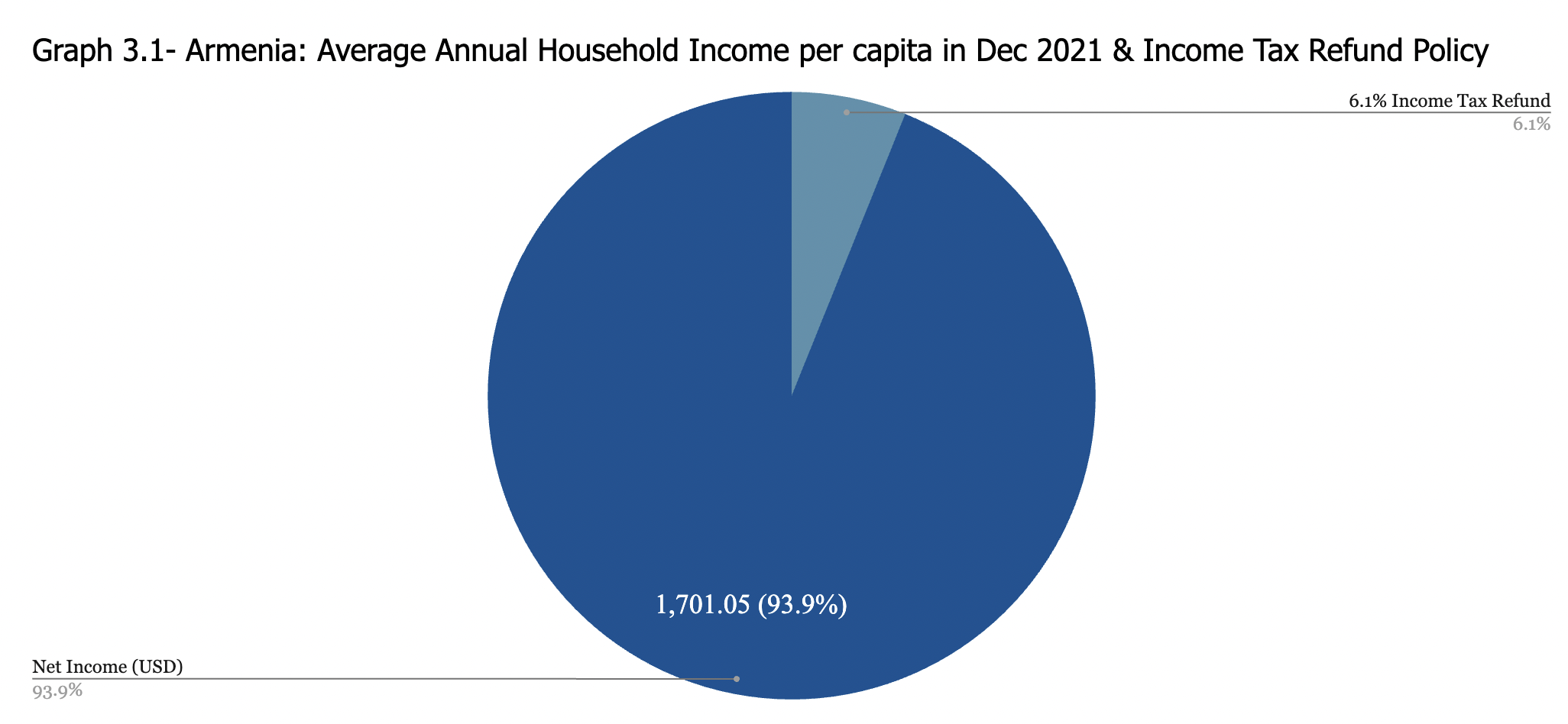

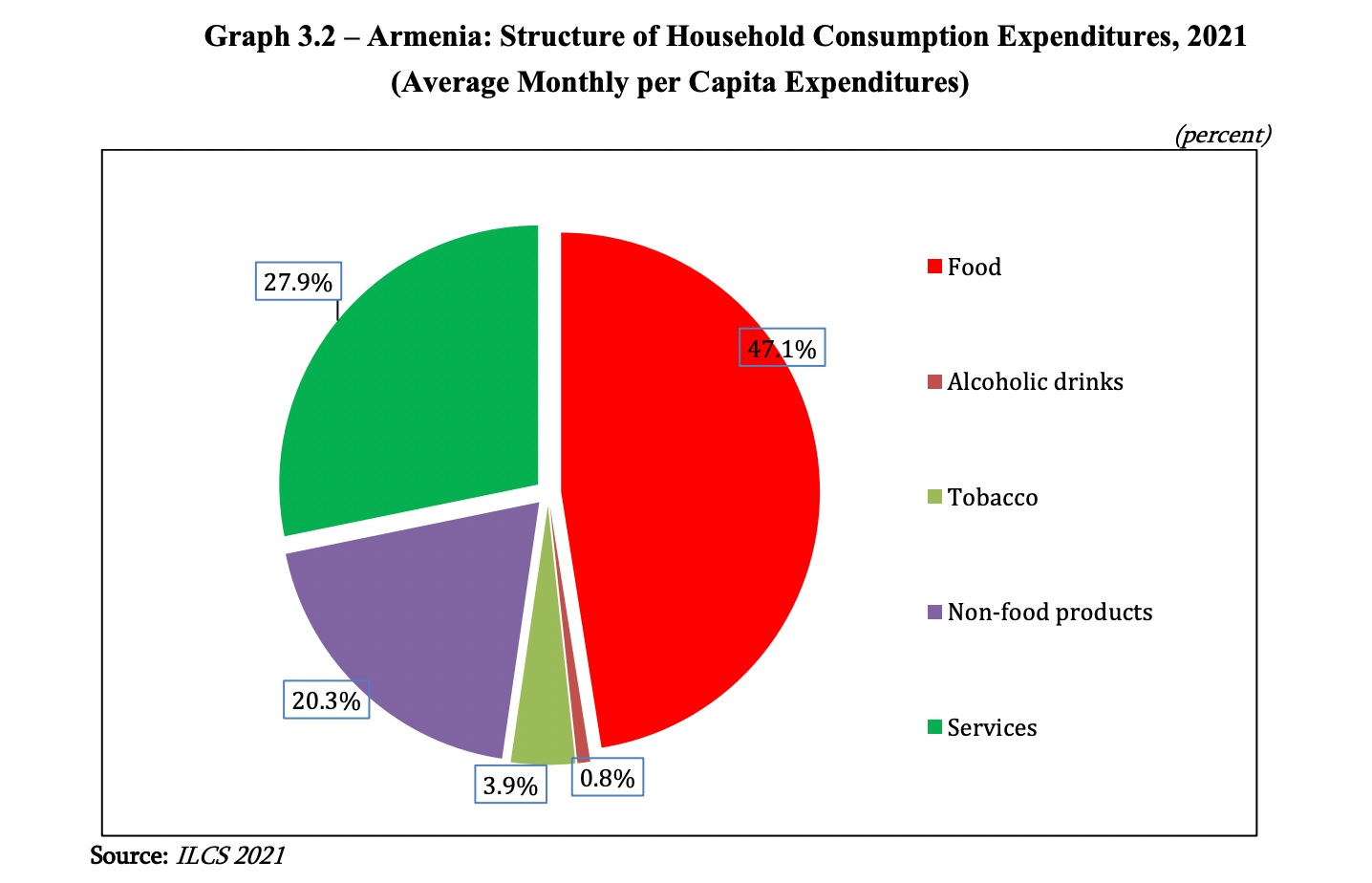

Second, the government should fund locals and implement a taxing policy, including government funds or tax revenue, to help locals and lower the cost of living. If an average Armenian works a job that pays around $400-500, then that is not even enough to rent a one-bedroom apartment. Mr. Khandamiryan says, “It’s just enough for you to rent a studio outside of the city center (Yerevan). In my opinion, there should be a policy that would either make housing less affordable for non-citizens, or the government itself should create housing opportunities that would provide affordable housing for people who are struggling with that”, just like the aforementioned income tax refund policy to make mortgage payments.[33] Policies that would help average families buy a house without spending their entire paycheck on paying rent would be ideal. Graph 3.1 is a pie chart that illustrates the average annual household income per capita in December of 2021 and how much of it is taxed through the income tax refund policy, which was 6.1% in 2021.[34] Graph 3.2 shows household consumption expenditures in 2021.

“According to available data, the share of expenses on food (47.1%) and services (27.9%) within consumption expenditures of the population are significant.”[35]

“According to available data, the share of expenses on food (47.1%) and services (27.9%) within consumption expenditures of the population are significant.”[35]

Third, systematically increasing legal average wages and creating more competitive markets is a more fundamental policy that could help alleviate this issue. “Rather than just solving the symptoms of the issue, we need to treat the cause of the issue. And the cause is that jobs are having a hard time catching up with the cost of living,” Mr. Khandamiryan remarks.[36] If the big entry barriers in many markets are removed, and people are incentivized to enter the market because it’s less costly, then Armenia could have more properly functioning competition. There would be less concentration within a few industries, and the cost of living would be corrected.

Fourth, the government needs to work on increasing the number of high-skilled jobs and having a strong educational institution that creates professionals ready to work in the job market. If one high-skilled job creates four low-skilled jobs, then Armenia must use that to its advantage. Mr. Khandamiryan explains, “One of the reasons why Silicon Valley has a booming job market is because the high-skilled job opportunities have created a high demand for low-skilled labor and incentivized low-skilled labor. I think if the government prioritizes creating scientific research opportunities, that would bring in researchers and high-skilled labor, which would further incentivize interests in other industries.”[37]

Finally, providing more educational opportunities for Armenians seeking higher education could later create more job opportunities and pull families out of poverty. So many highly educated Armenians come to study and teach in privileged U.S. institutions, but Gevorg Khandamiryan explains that there is no government-centralized approach to bring them back to Armenia and support the job market there, promote research, and provide more high-skilled jobs. If the diaspora is more engaged in higher education, all other industries suddenly have to catch up. Mr. Khandamiryan emphasizes that the government needs to invest in education and research in the country if it hopes to alleviate families’ poverty levels.

Furthermore, Mr. Khandamiryan proposes another point of view regarding the influx of immigrants and forcibly displaced people from their native lands in Artsakh. Although it is a big tragedy, these people have much potential and possible talents. However, because Armenia does not have enough educational opportunities, people leave and study abroad– contributing to the brain drain in the country. Then, if they come back to Armenia, they cannot get a job with pay that meets their financial needs. He continues, “If we look at Greece, which has also been struggling a lot in terms of the influx of immigration of Palestinian people, they are implementing this policy that offers people who are studying abroad salary subsidies so that they are incentivized to come back and work in Greece.”[38] Although Armenia is trying to do the same thing and is giving subsidies of up to 70% of one’s salary if they come back and work, it’s not properly scaled, and not enough people know about it. Mr. Khandamiryan suggests that if it were to reach people in the diaspora, it would succeed. He further explains, “You need hundreds of these types of people for the policy to succeed. The government cannot ignore spillover effects; we need enough people [in Armenia] to do research and be in higher education to incentivize others to stay and better the country.”[39]

In the United States, the effects of inflation are indexed away through cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) in employment contracts. The United Kingdom, Ireland, and Canada use adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), which vary the interest rate people pay according to inflation. Thresholds for deferral marginal income tax rate brackets are also put in place in the U.S.; federal tax brackets make it so that as one gets richer, the tax that they pay on each marginal dollar goes up.[40] Thus, Armenia could implement similar policies to mitigate the effects of high inflation. Like most other post-Soviet states, Armenia is currently implementing a flat tax rate of 19%. The flax tax rate started at 23% on January 1, 2020, and has been steadily decreasing since.

To conclude, 23% of families in Armenia are living below the poverty line due to the aftermath of the 1988 Spitak Earthquake, remnants of the Soviet Union and its surviving economic system, current geopolitics with neighboring states, high rental rates, rising inflation, and failures of social security efforts. If we wish to reduce poverty in Armenia and the proportion of families living below the poverty line, the government must implement price discrimination policies in the housing market, a taxing policy to lower the cost of living, systematically increase legal average wages and create more competitive markets, increase the number of high-skilled jobs, and provide more educational opportunities.

https://www.atlasandboots.com/travel-blog/best-day-trips-from-yerevan-armenia/ ↩︎

New East network, “Post-soviet World: What You Need to Know About Armenia”, The Guardian, 6/9/14, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/09/-sp-post-soviet-world-need-to-know-armenia. ↩︎

NA, "Republic of Armenia: Country Data", International Monetary Fund, 10/23, https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/ARM. ↩︎

NA, "Real GDP growth", International Monetary Fund, 2023, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/MEQ/ARM. ↩︎

New East network, “Post-soviet World: What You Need to Know About Armenia”, The Guardian, 6/9/14, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/09/-sp-post-soviet-world-need-to-know-armenia. ↩︎

Seda Hergnyan, "Armenia's 2021 Poverty Rate Was 26.5%, Says Government Agency", hetq, 11/30/22, https://hetq.am/en/article/150676. ↩︎

Samson Okalow, "What is poverty? It's not as simple as you think", World Vision, 4/5/23,https://www.worldvision.ca/stories/child-sponsorship/what-is-poverty#:~:text=Nearly 719 million people around,as clean water or nutrition. ↩︎

NA, "The World Bank in Armenia", The World Bank, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/armenia/overview. ↩︎

NA, "IMF Country Reports: Republic of Armnia: 2023 Article IV Consultation and Second Review", International Monetary Fund, December 2023,https://www.elibrary.imf.org/downloadpdf/journals/002/2023/416/002.2023.issue-416-en.xml. ↩︎

Marc Champion and Tony Halpin, "What's Nagorno-Karabakh and Why Do Azerbaijan and Armenia Fight Over it?", The Washington Post, 9/20/23, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/energy/2023/09/20/nagorno-karabakh-why-do-azerbaijan-and-armenia-dispute-it/457d65d4-57bb-11ee-bf64-cd88fe7adc71_story.html. ↩︎

Nanna Heitmann, https://nannaheitmann.com, https://www.instagram.com/nannaheitmann?igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==. ↩︎

https://massispost.com/2023/09/more-than-50000-karabakh-armenians-have-fled-to-armenia/. ↩︎

Alex Galitsky and Gev Iskajyan, "The U.S. Keeps Failing Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh", Time Magazine, 9/20/23, https://time.com/6316001/us-failures-nagorno-karabakh/. ↩︎

Marc Champion and Tony Halpin, "What's Nagorno-Karabakh and Why Do Azerbaijan and Armenia Fight Over it?", The Washington Post, 9/20/23, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/energy/2023/09/20/nagorno-karabakh-why-do-azerbaijan-and-armenia-dispute-it/457d65d4-57bb-11ee-bf64-cd88fe7adc71_story.html. ↩︎

ANCA, "Senate Unanimously Adopts Bill Blocking US Military Aid to Azerbaijan", The Armenian Weekly, 11/16/23,https://armenianweekly.com/2023/11/16/senate-unanimously-adopts-bill-blocking-us-military-aid-to-azerbaijan/. ↩︎

Dzovinar Derderian, (Assistant Adjunct Professor in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley). Interview with Dzovinar Derderian. 10/20/23. ↩︎

Dzovinar Derderian, (Assistant Adjunct Professor in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Dzovinar Derderian, 10/20/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

Kendrick Foster, "Armenia's Velvet Revolution: Lessons from the Caucasus", Harvard International Review, 5/29/19, https://hir.harvard.edu/armenias-velvet-revolution/#:~:text=In April of this year,evoking the successful Czechoslovak Velvet. ↩︎

NA, "Modern Economic History", U.S. Library of Congress, https://countrystudies.us/armenia/34.htm#:~:text=The Stalinist command economy%2C in,the Soviet government in 1991. ↩︎

NA, "Modern Economic History", U.S. Library of Congress, https://countrystudies.us/armenia/34.htm#:~:text=The Stalinist command economy%2C in,the Soviet government in 1991. ↩︎

Dzovinar Derderian, (Assistant Adjunct Professor in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Dzovinar Derderian, 10/20/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

NA, "Poverty and Food Security: A Snapshot of Interlinkages", World Food Programme, March 2023,https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000147506/download/?_ga=2.162055996.1645824387.1687452003-1958358100.1687452003. ↩︎

NA, "Poverty and Food Security: A Snapshot of Interlinkages", World Food Programme, March 2023,https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000147506/download/?_ga=2.162055996.1645824387.1687452003-1958358100.1687452003. ↩︎

NA, "Poverty and Food Security: A Snapshot of Interlinkages", World Food Programme, March 2023,https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000147506/download/?_ga=2.162055996.1645824387.1687452003-1958358100.1687452003. ↩︎

NA, "Poverty and Food Security: A Snapshot of Interlinkages", World Food Programme, March 2023,https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000147506/download/?_ga=2.162055996.1645824387.1687452003-1958358100.1687452003. ↩︎

Dzovinar Derderian, (Assistant Adjunct Professor in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Dzovinar Derderian, 10/20/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

Dzovinar Derderian, (Assistant Adjunct Professor in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Dzovinar Derderian, 10/20/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

International Monetary Fund. Fiscal Affairs Dept., "Republic of Armenia: Technical Assistance Report on Personal Income Tax: Policy Review and Introduction of a Universal Declaration", IMF eLibrary, 1/30/23, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2023/060/article-A001-en.xml. ↩︎

ILCS, "Armenia- Household Income, Expenditures, and Basic Food Consumption", Armstat, 2021, https://armstat.am/file/article/poverty_2022_en_3.pdf. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

Gevorg Khandamiryan, (Economics Graduate Student Instructor at the University of California, Berkeley), Interview with Gevorg Khandamiryan, 11/3/23. ↩︎

Jim Campbell (Lecturer in the Department of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley), Econ 1 Lecture, Topic 10: Measuring the Macroeconomy, Fall Semester 2023. ↩︎