Why Teenage Mental Health Is Spiraling

The United States has a new pandemic that it has to deal with: a significant increase in depression among adolescents, particularly girls.[2] After the publication of a CDC bi-annual Youth Risk Behavior Survey–claiming that teens are experiencing record levels of depression and suicide rates–multiple organizations are trying to find the reasons behind such a spike.[3] Finding out why adolescents' mental health has been declining in recent years can help us prevent it from worsening. Since 2021, adolescents have been significantly more depressed than in past years because of increased social media consumption and its varying effects on different gender, ethnic, and sexuality groups, poor quality interpersonal relationships with peers, and stressors incited by global political and societal issues.

Mental health taboos and stigmas have often kept those suffering from reaching out to others and seeking help. Such taboos can be public stigmas, self-stigmas, or a combination of the two. Public stigmas are stereotypes that the general population holds that can be used to discriminate against others. When someone is reduced to their symptoms or diagnosis and is thus not seen as a whole person, their mental health has been stigmatized. For example, if one is called “psychotic”, they are being reduced to the mental health issue they suffer from. If someone is mocked or called weak for seeking help, it’s also a stigma. Furthermore, it’s a stigma when a person’s mental illness is downplayed. For example, those with anxiety may be labeled as cowardly, those with depression may be told to “snap out of it”, and those with schizophrenia “may be incorrectly described as having a ‘split personality’”.[4] In general, those with mental illnesses can be seen as more violent than the rest of society. Despite this, health agencies, the criminal justice system, employers, schools, and the media are taking measures to destigmatize mental health and topics pertaining to it. In the past two decades, more people have been getting educated on various illnesses, and many believe treatment is effective. However, this prompts the question: If more people are talking about mental illnesses, then why have adolescents’ mental health recently declined so dramatically?

Impact on Various Gender, Ethnic, and Sexuality Groups

Some groups of teens are more vulnerable to threats, violence, and influence from others virtually and in person. The impact of social media also varies based on one’s gender, ethnicity, and sexuality. The 2021 CDC survey illustrates that ⅗, or 57%, of girls and 29% of boys in the U.S. reported feeling sad or hopeless. The metric for girls represents a 60% increase since 2021 and a 36% rise from the previous decade.[5] Furthermore, there are high levels of violence, depression, and suicidal thoughts among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. More than ⅕ of these students reported attempting suicide the year before the survey. Additionally, research shows that bisexual individuals are more at risk of negative mental health problems compared to monosexual (heterosexual and homosexual) individuals because of stress related to stigma and discrimination, including biphobia, monosexism, and bi-erasure. Moreover, every year, 1 in 5 women in the U.S. have a mental health problem, like PTSD, an eating disorder, or depression. [6] Although men and women have similar rates of mental health issues, the types of problems may differ. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, while rates of mental health disorders are similar between people of color and whites, people of color suffer from such illnesses for a longer period of time. Also, most “mental illnesses go untreated, especially in communities of color. Fifty-two percent of Whites with AMI received mental health services in 2020, compared to 37.1% of Blacks and 35% of Hispanics”.[7] According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), this is due to an “inaccessibility of high quality mental health care services, cultural stigma surrounding mental health care, discrimination, and overall lack of awareness about mental health” for racial/ethnic, gender, and sexual minorities.[8]

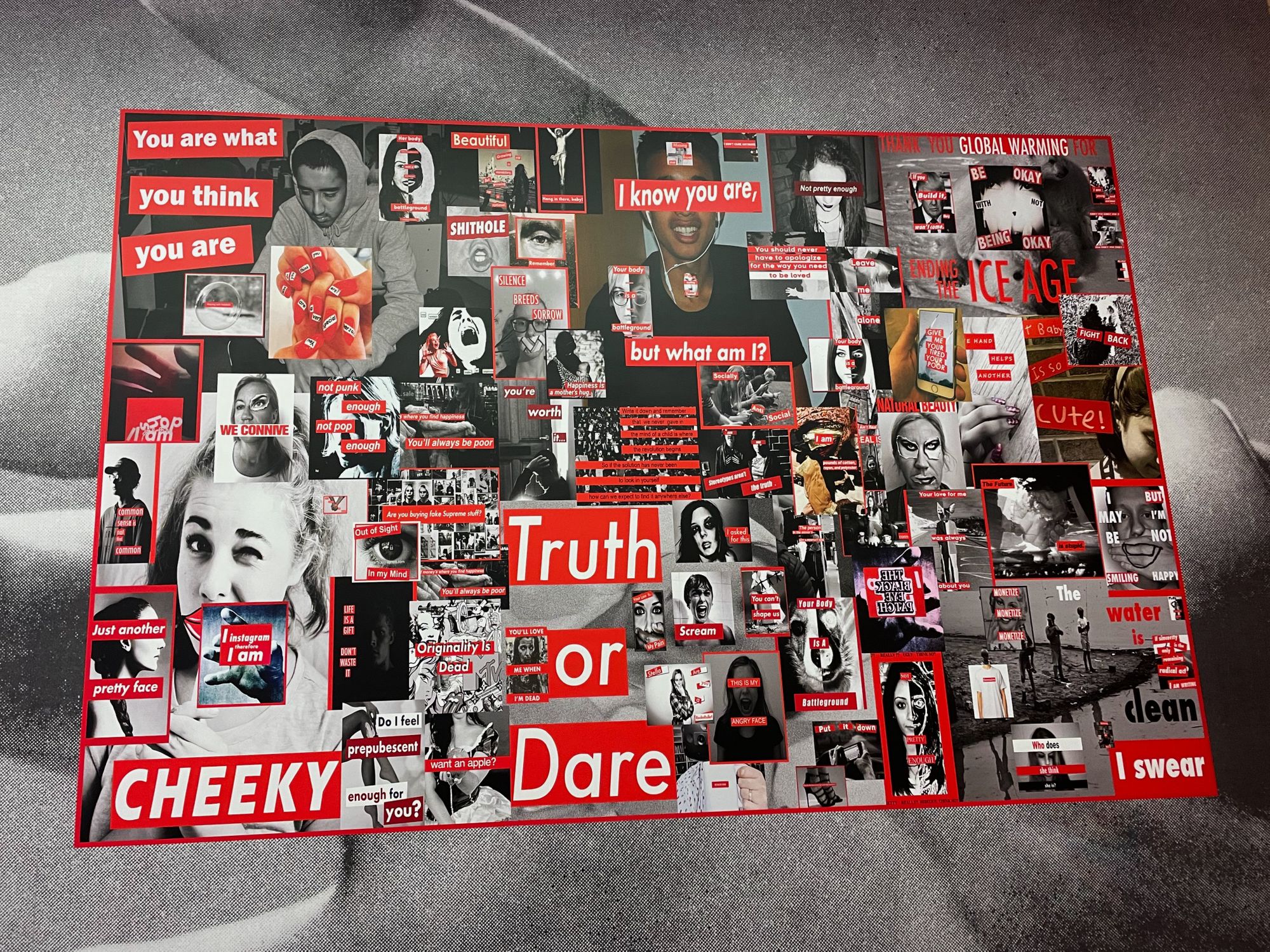

Art by BARBARA KRUGER, Medium: Photography, sculpture, graphic design, architecture, Photo taken by author at The Art Institute of Chicago, November 13, 2021.

Art by BARBARA KRUGER, Medium: Photography, sculpture, graphic design, architecture, Photo taken by author at The Art Institute of Chicago, November 13, 2021.

Regarding social media consumption, boys and girls are exposed to unattainable beauty standards daily. A 2019 study of 6,500 12- to 15-year-olds conducted in the United States found that “those who spent more than three hours a day using social media might be at heightened risk for mental health problems”.[9] In the same year, a study of 12,000 13- to 16-year-olds in England found that those “using social media more than three times a day predicted poor mental health and well-being in teens”.[10] Such statistics can be attributed to the unattainable beauty standards that many social media platforms normalize and glorify. Such standards are perpetuated through edited posts or the use of filters by influencers. In an opinion piece by Jon Haidt, a social psychologist, he claims that the transition from a play-based childhood to a phone-based childhood in the 2010s has kept kids from normal human development. Before, a play-based childhood, which involved some risky, unsupervised play, would allow children to overcome various fears and learn how to interact with others. However, since the invention of the smartphone, children’s time spent on it has kept them from sleeping, playing, and socializing, and it causes addiction among many. It also causes adolescents to compare themselves to others online- which is a distorted reality.[11]

So what can we do about all this? How can we prevent mental health disparities between people of differing genders, ethnicities, and races, and what can we do to mitigate the negative consequences of social media use? The APA suggests that doctors can start by understanding a patient’s culture and background to provide the highest quality of care. Also, utilizing the DSM-5 Handbook of the Cultural Formulation can help clinicians consider the influence of one’s culture in their work “to enhance the patient-clinician communication and improve outcomes”.[12] The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) is currently committed to working with various communities, organizations, and policymakers to break the systemic racism and historical barriers and inequities that have affected our healthcare system in the U.S. They also aim to ensure that “mental health resources…are culturally relevant [and are] equitably available across the nation”.[13] Regarding social media, avoiding scrolling for hours and staying present and connected with others in real life can help mitigate its effects on one’s self-esteem and overall mental health. Pay attention to how you feel after consuming media: Do you feel happy or jealous after seeing pictures of friends at a party? Are you stressed or informed after reading/watching the news? Figuring out why you are online and how it makes you feel can allow you to set time limits on social media apps, unfollow/report those that intentionally negatively affect you, and mute those that unintentionally negatively affect your emotions. Remember that not everything on social media is real, but its effects are, so it is imperative that we protect ourselves and others online. Rather than merely interacting with friends online, call them and ask to meet up and see how they are doing. Living in the moment and having in-person conversations and contact with people can greatly improve one’s mental health, as well as partaking in activities like meditation, exercise, or calling friends and family.[14]

Interpersonal Relationships

What marks adolescence is the growth in the importance of peer relationships. Depression levels also continue to rise throughout adolescence and until adulthood. Thus, it is speculated that negative interpersonal relationships are another cause of why adolescents are significantly more depressed. Past negative experiences with parents, teachers, peers, and friends can influence one’s mental health. The developmental psychology and interpersonal theories of depression emphasize the relationship between an individual and one’s social environment. Theory suggests that relationships of low quality can severely disrupt adolescents’ normal development processes, like identity development, emotional functioning, and social skills, and can lead to depression.[15] It is also possible for the opposite transactional association to be true- if one is initially depressed, relationship quality may worsen.

In a study conducted by Caroline W. Oppenheimer, a Suicide Prevention Research Scientist at the Research Triangle Institute (RTI), and Benjamin L. Hankin, a psychology professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, a “multi-wave design [was used] to examine the short-term longitudinal and bidirectional associations between depressive symptoms and peer relationship qualities”.[16] The 350 students total– a sample that consisted of early to middle adolescents (between 6th grade and 10th grade) of different races, ethnicities, and genders– completed self-reports three different times, all five weeks apart. The reports measured relationship quality and depressive symptoms, and results indicated that such symptoms predicted increases in negative relationship qualities and decreases in positive qualities, but neither positive nor negative qualities increased depressive symptoms. Essentially, it was found that if a depressed individual expresses characteristics and behaviors that bring about problems in their relationships, these maladaptive relationships will lead to more depressive symptoms over time.[17] The students, all from Chicago-area schools, participated upon their own accord, and 390 out of 497 interested students were provided active consent from their parents. 350 students total provided complete data at baseline. Various school districts and their institutional review boards, school principals, classroom teachers, and the university institutional review board all gave the researchers permission to conduct this investigation. The self-reports used in the study included the Children’s Depression Inventory and the Network of Relationships Inventory.[18] The CDI is a self-report measure that evaluates depressive symptoms in children and adolescents using 27 items. Internal reliability in youth in this sample was α = 0.91.[19] The NRI is also a self-report measure that usually uses 30 items to assess relationship quality. In this study, 13 items were used in the NRI, and the only responses available to select were the responses: same-sex friend, other-sex friend, and romantic partner. Internal reliability for this sample was α = 0.86. The NRI included seven items examining positive relationship qualities, asking questions like “How much do you play around and have fun with this person?”, or “How much does this person help you figure out or fix things?”, and six items assessing negative qualities like “How much do you and this person disagree and quarrel?”, or “How much do you and this person get upset with or mad at each other?”[20]

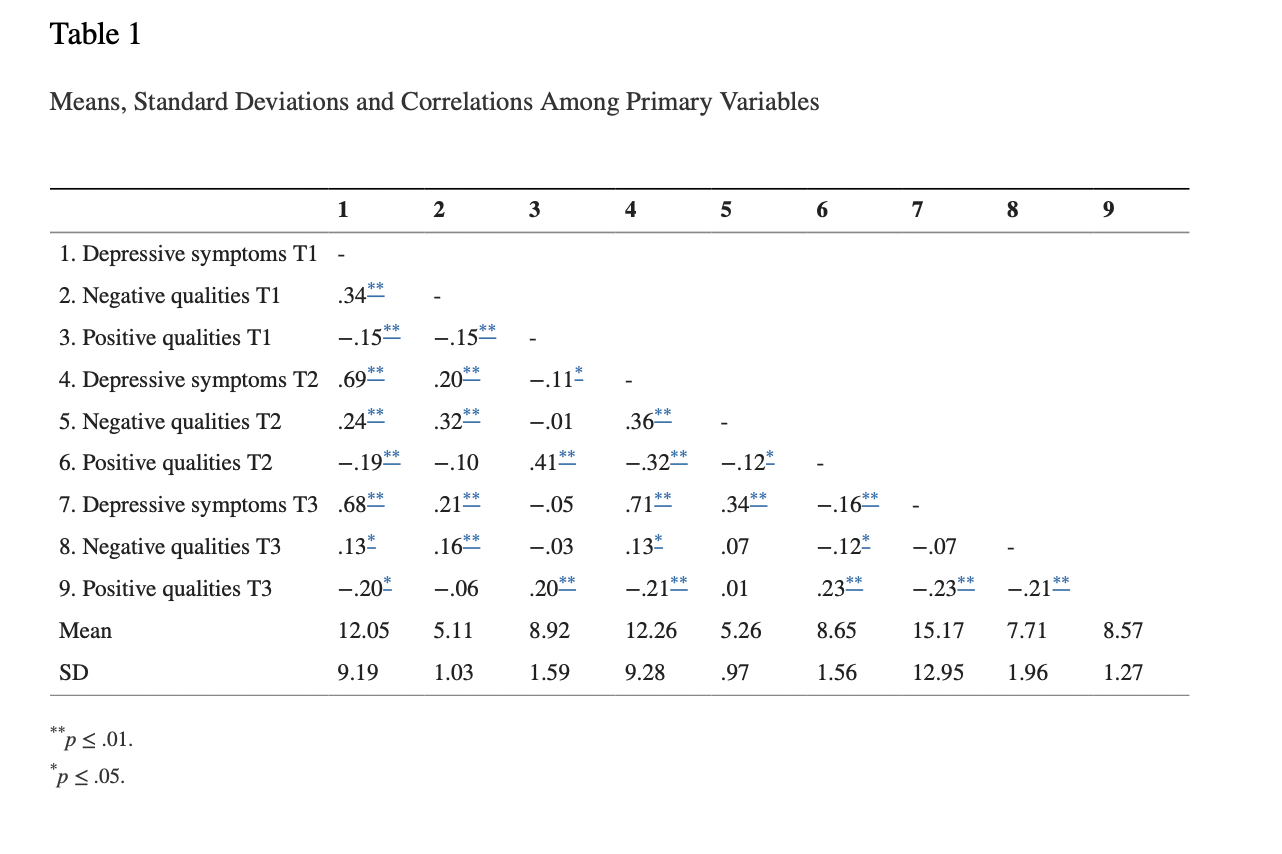

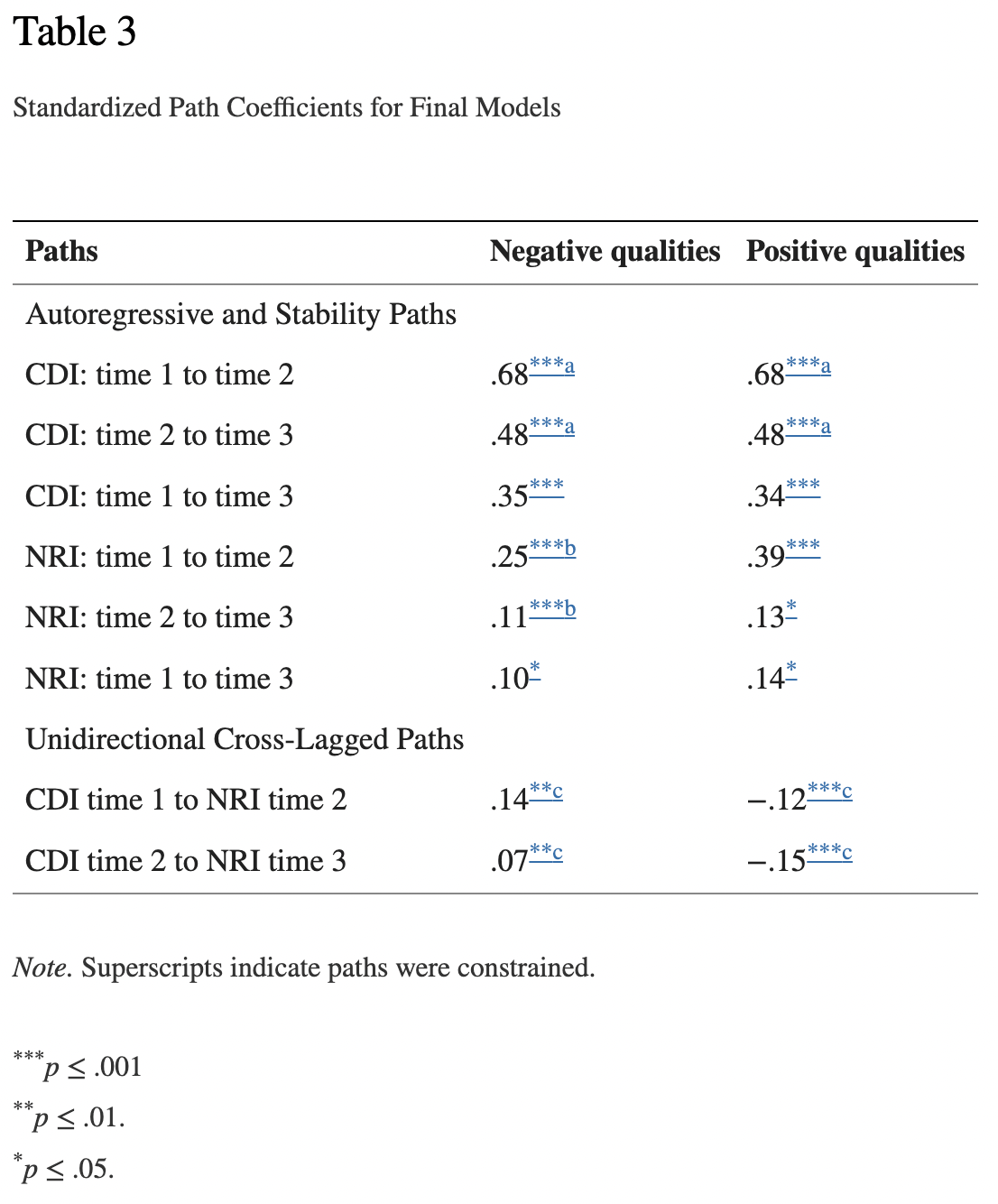

Table 1 illustrates the descriptive statistics and correlations of the main variables of the study. In an author manuscript describing the research study, Oppenheimer and Hankin write, “Crossed-lagged effects structural equation models (SEM) using AMOS 16.0 were used to test transactional associations between depressive symptoms and relationship quality over time”. Negative and positive qualities in relationships were put into separate models. First, the researchers fitted a baseline model that included only autoregressive effects and stability paths. Then, they compared that baseline model to a unidirectional model with paths from the CDI and NRI self-reports. Finally, they “compared the full bi-directional model to the unidirectional model. Chi-square difference tests were used to compare competing models”.[21] To see if the best fitting model for positive or negative relationship quality was affected by age or gender, a multigroup comparison approach was used. To test age as a moderator, a median split was used to create groups. Oppenheimer and Hankin write, “Chi-square difference tests revealed that neither age nor gender moderated associations for either model. Therefore, the following analyses are presented for the overall sample.”[22]

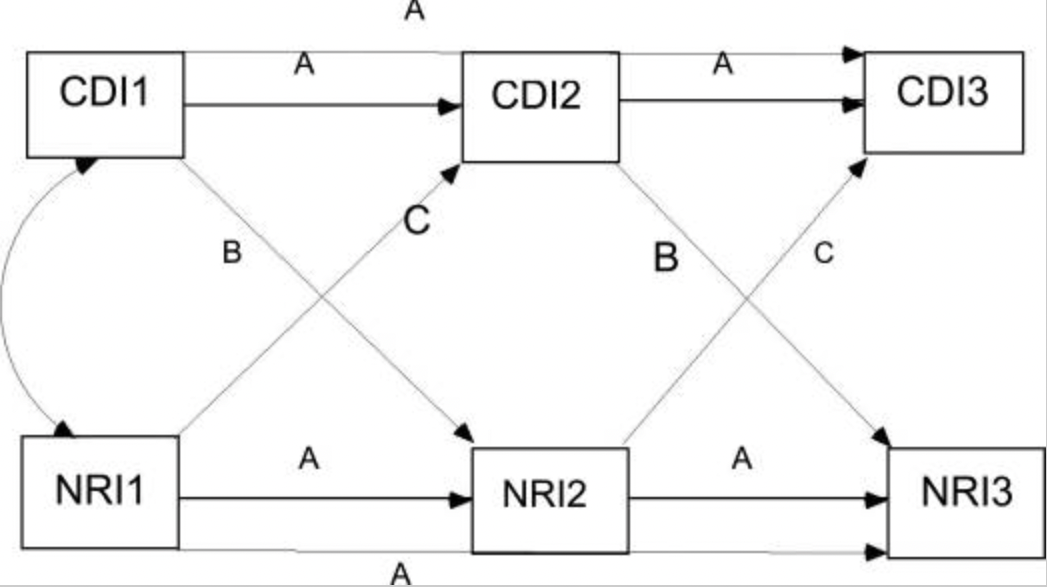

Table 2 illustrates fit statistics for this model. It was found that the “unidirectional model, with paths from CDI to NRI, was the most parsimonious model. These unidirectional paths from CDI to later NRI were consistent across time as a constrained unidirectional path model did not differ from an unconstrained model, χ2 (1) = .05, p =.82”.[24] Table 3 shows the positive and significant constrained unidirectional paths from CDI to NRI reports.

*A: Paths included in the baseline models. B: Paths included in the unidirectional model, in addition to all paths in the baseline model. C: Paths included in bidirectional model, in addition to all paths in baseline and unidirectional model. *[25]

*A: Paths included in the baseline models. B: Paths included in the unidirectional model, in addition to all paths in the baseline model. C: Paths included in bidirectional model, in addition to all paths in baseline and unidirectional model. *[25]

Ultimately, Oppenheimer and Hankin's research study showed that depressive symptoms were associated with poor relationship quality over time. This finding was true for both boys and girls that were both early and middle adolescents. The researchers write, “These results are consistent with prior research and theory proposing that characteristics and behaviors associated with depression disrupt interpersonal functioning. The findings specifically suggest that depressive symptoms interfere with the formation of high quality peer relationships.”[26] This study’s findings were also the first to indicate that poor relationship quality by itself does not increase depressive symptoms. However, other risk factors can exacerbate poor relationship qualities, which in turn can predict increases in depressive symptoms.

How can we ensure that young adolescents do not find themselves in poor relationships? How can we give them the help that they need from the onset of depressive symptoms so that it doesn’t negatively affect their interpersonal relationships? Some suggest that school interventions from teachers and an awareness that depressive behaviors, characteristics, and symptoms can interfere with the formation and maintenance of high-quality peer relationships would be an effective way to treat adolescent depression. Clinical interventions, such as interpersonal psychotherapy, would also be effective. To ensure that adolescents are in positive relationships and surround themselves with people that truly care for them, parents and caretakers should encourage good relationship modeling, be open to discussing sex and the elements of a healthy romantic relationship, monitor media use, and be flexible in their approach to educating and supporting their adolescent(s).[27] As mentioned above, interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents is an effective way to help those that exhibit depressive symptoms so that it prevents the unraveling of their platonic and/or romantic relationships. Also known as IPT-A, individual interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents from the ages of 12-18 that suffer from depression consists of 12–16 sessions.[28] Its goals include helping adolescents to process and recognize their feelings and think about how interpersonal conflicts might affect them, improve their communication and problem-solving skills, enhance their social competency and skills, lessen stress experienced in relationships, and decrease depressive symptoms. Sessions last for about 45-60 minutes, and therapists might also meet with parents or guardians for 1-3 sessions.

Global Political and Societal Issues

Furthermore, it is speculated that global political and social issues over the past few years have caused adolescents to undergo more stress. Constantly changing societal norms and the onslaught of political issues that have recently arisen put a lot of pressure on adolescents and have negatively affected their mental health. For example, the rise of the global pandemic in 2020, as well as social movements like Black Lives Matter, which sought to raise awareness about the institutionalized racism in our political and carceral systems, are two events that defined the year and left many feeling angry and even hopeless. For the past three years, the feelings that were brought about during these movements still remain for many.

To assess the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic that came about in 2020 and its impact on the mental health of adolescents, UNICEF, a humanitarian aid global nonprofit organization, conducted a recent poll. It found that the COVID-19 crisis is significantly impacting the mental health of adolescents in Latin America and the Caribbean. The poll questioned 8,444 adolescents and young people from the ages of 13 to 29 in nine countries and territories in the region.[29] Participants were asked how they felt during the first months of the pandemic. It was found that 27% reported feeling anxiety and 15% depression in the last seven days. Additionally, 46% of adolescents reported having less motivation to do enjoyable activities, and 36% felt less driven to do regular chores. Interestingly, women felt more pessimistic about the future (43%) compared to their male counterparts (31%). To cope with these feelings, many adolescents reported partaking in activities that allowed them not to think about the pandemic, like helping in a community kitchen, reading, writing, and exercising more.

In the United States, a CDC report in 2021 found that 37% of high school students reported experiencing “poor mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 44% reported they persistently felt sad or hopeless during the past year”.[30] A lack of school connectedness during quarantining negatively affected adolescents’ mental health. Findings highlighted that feeling supported, cared for, and a sense of belonging at school was extremely important to students. Thus, not going to school in person lessened teens’ school-connectedness.

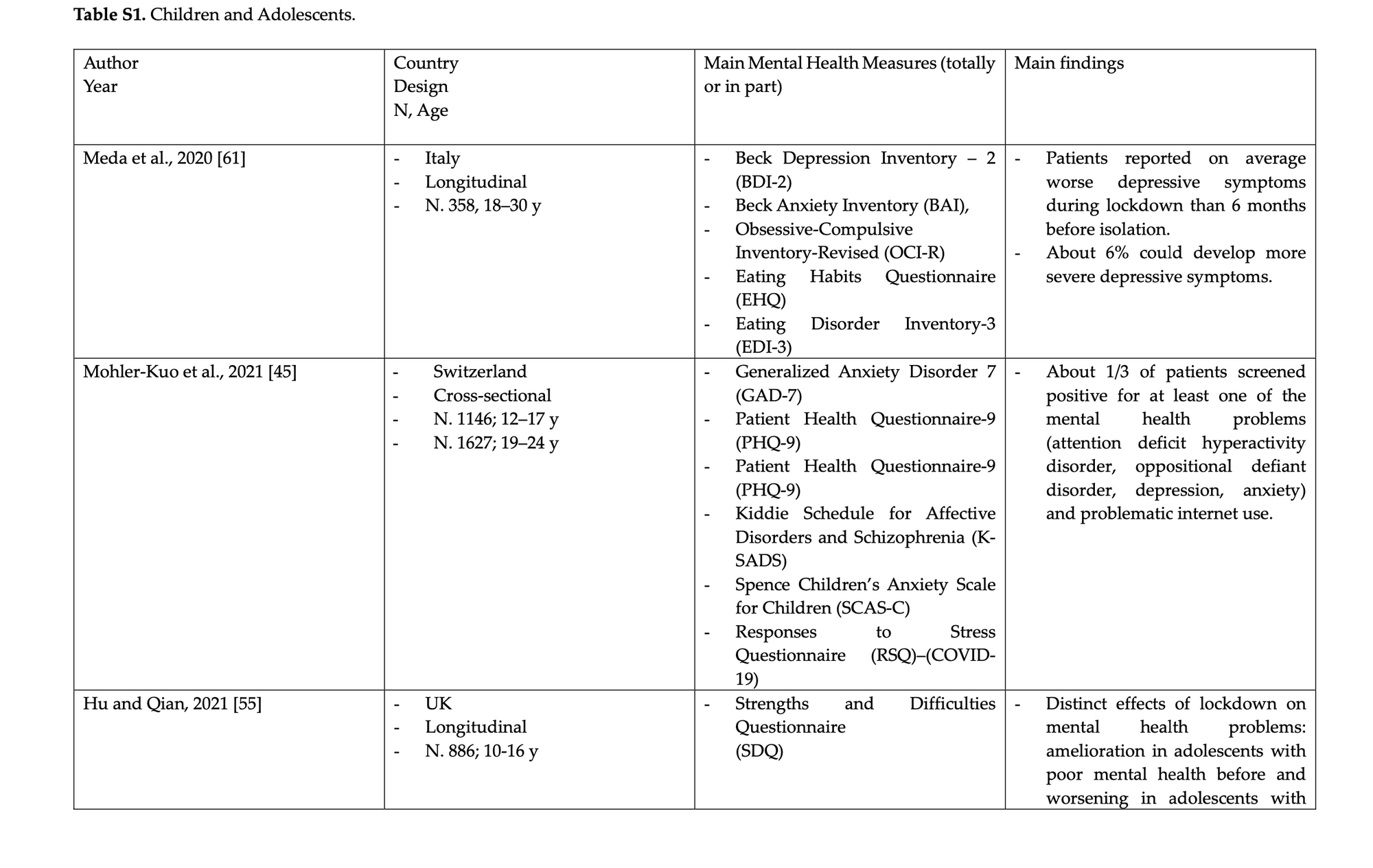

A study in 2022 aimed to evaluate the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. The population was analyzed by age group, and it was found that youth were the most affected. Females had a higher prevalence of psychopathological symptoms; this was due to the “poor social support, economic difficulties, and, in particular, unemployment or job changes” that the pandemic incited.[31] Other risk factors were a perception of loneliness, pre-pandemic mental illness, and maladaptive coping strategies. It was found that about ⅓ of adolescents had “significant emotional disorders related to the stress provoked by the pandemic and related restrictions, exhibiting symptoms of anxiety and depression”.[32] The visualization below illustrates the first portion of a table that summarizes the findings of each researcher based on the country and age group studied, design used, mental health measures used, and main findings. Most studies had a cross-sectional design, and only a few made a comparison with time periods before the pandemic.

To view the full Table S1 of Children and Adolescents, visit: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19159347/s1

To view the full Table S1 of Children and Adolescents, visit: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19159347/s1

Finally, this study recommended that institutional interventions should be considered to better support adolescents in Europe whose mental health was negatively affected by the global pandemic. Territorial support and the use of new technologies should be used in the field of mental health care as well.

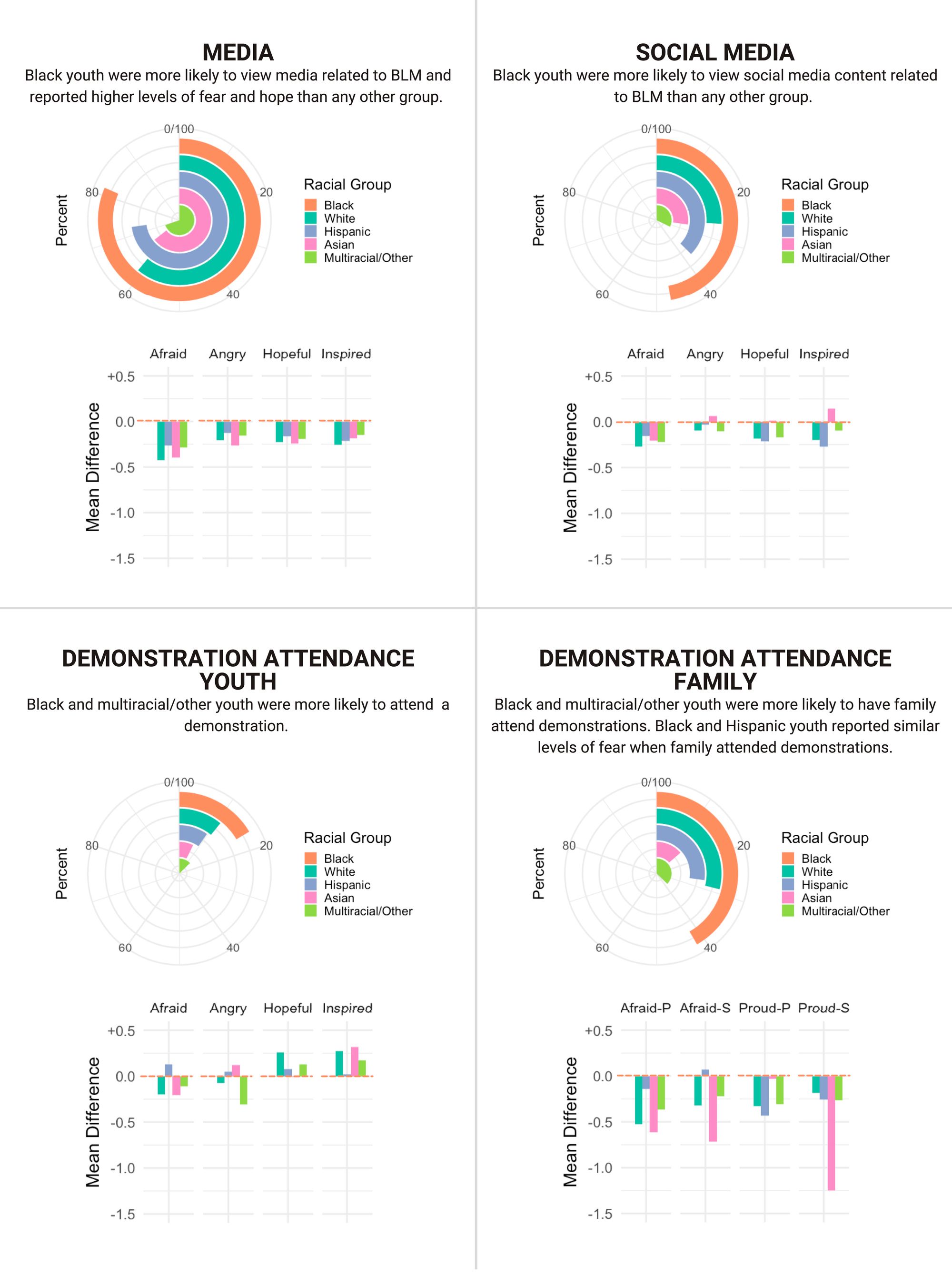

Regarding the Black Lives Matter social movement, it was found that adolescents under 18 years old were increasingly involved in the movement. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a peer-reviewed journal of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), used a large-scale quantitative survey to assess how media and in-person involvement in the social movement affected adolescents of different ages and races. In the first survey of adolescents’ exposure to BLM demonstrations, “4,970 youth (mean age = 12.88 y) across the United States were highly engaged, particularly with media, and experienced positive emotions when exposed to the BLM movement”.[33]Additionally, Black teens reported higher negative emotions when engaging with various forms of media and were exposed to more violence during in-person BLM demonstrations. The stacked donut plots below illustrate the frequency of engagement with different types of media, in-person, and family demonstration. The bar charts display the difference between the mean feelings for Black adolescents and each racial/ethnic group regarding the forms of engagement.

“Stacked donut plots display the frequency of engagement with TV/radio/Internet media, social media, in-person demonstration (recoded as attend/not attend for visualization), and family demonstration attendance (recoded to combine parent and sibling for visualization). Bar charts display the difference between the mean feelings for Black adolescents and each racial/ethnic group for each mode of engagement (0.0 on the y axis [orange] represents the Black adolescent mean; positive values indicate Black adolescents report lower levels of positive or negative feelings; negative values represent Black adolescents report higher levels of positive or negative feelings)”.[34]

“Stacked donut plots display the frequency of engagement with TV/radio/Internet media, social media, in-person demonstration (recoded as attend/not attend for visualization), and family demonstration attendance (recoded to combine parent and sibling for visualization). Bar charts display the difference between the mean feelings for Black adolescents and each racial/ethnic group for each mode of engagement (0.0 on the y axis [orange] represents the Black adolescent mean; positive values indicate Black adolescents report lower levels of positive or negative feelings; negative values represent Black adolescents report higher levels of positive or negative feelings)”.[34]

Thus, it is important that we not only appreciate youth civic engagement but also provide support for them when processing such complex experiences and feelings. It will benefit their mental and physical health and the welfare of society as a whole.

Concluding Remarks

We have much work to do on the international scale regarding supporting and protecting adolescents and their mental health during times of global political and social turmoil. In middle-income countries, three main approaches have been used to improve people’s mental health. The first combines prevention and treatment by integrating it into existing health services. The second approach is one of human rights– it emphasizes “the deinstitutionalization of people with chronic mental disorders and draws on the traditions in the West, as pioneered in Trieste, Italy in the 1970s and 1980s”.[35] The third is a developmental approach that aims to reduce poverty to expand access to healthcare. The idea is that if more people have access to healthcare, national wealth will increase, and people’s overall mental health will improve.

These three approaches require careful monitoring and evaluation so that they can work well. Countries not only need more resources, but these assets need to be implemented strategically. For example, because many social determinants influence mental health, rehabilitative interventions need to address poverty reduction as well. An article from the National Library of Medicine states, “Livelihood interventions are increasingly being linked to mental health interventions, as demonstrated by the NGO BasicNeeds UK in Uganda, and to psychosocial interventions such as those offered by the Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation – Uganda– in small pilot projects”.[36] Such evidence illustrates the intersection between mental health and poverty both in terms of causation and in establishing a view that will assist in developing needed interventions.

Currently, the World Federation of Mental Health is playing an essential role in organizing international action through its annual World Mental Health Days.[37] This significant increase in depression among adolescents is no surprise if we look at the increased use of social media, the effects of poor mental health on interpersonal relationships, and the stress that global political and social issues ignite. The publication of a CDC bi-annual Youth Risk Behavior Survey–claiming that teens are experiencing record levels of depression and suicide rates– is the wake-up call that the world needed to hear. We need to destigmatize mental health so that people who suffer in silence are given the resources and support they need.

*Article image:*Jenny Chang / BuzzFeed / Via buzzfeed.com ↩︎

Elizabeth Englander and Meghan McCoy, "Analysis: There’s a mental health crisis among teen girls. Here are some ways to support them," PBS New Hours, Feb 24, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/analysis-theres-a-mental-health-crisis-among-teen-girls-here-are-some-ways-to-support-them (accessed March 5, 2023). ↩︎

Azeen Ghorayshi and Roni Caryn Rabin, "Teen Girls Report Record Levels of Sadness, C.D.C. Finds", The New York Times, Feb 13, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/13/health/teen-girls-sadness-suicide-violence.html (accessed March 5, 2023). ↩︎

NA, "Mental illness stigma", healthdirect, Sept 2021, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/mental-illness-stigma#:~:text=Resources and support-,What is mental illness stigma%3F,a stain or a blemish (accessed March 5, 2023). ↩︎

Ghorayshi and Caryn Rabin, "Teen Girls Report Record Levels of Sadness, C.D.C. Finds", Feb 13, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/13/health/teen-girls-sadness-suicide-violence.html. ↩︎

NA, "Mental Health Disparities: Diverse Populations", American Psychiatric Association, 2023, https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/diversity/education/mental-health-facts (accessed April 23, 2023). ↩︎

Danielle Leblanc, "Black Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) Mental Health Fact Sheet", rtor.org, 2023, https://www.rtor.org/bipoc-mental-health-equity-fact-sheet/?gclid=CjwKCAjwiOCgBhAgEiwAjv5whFXevXYEnVlFOeXNB29gn5XjQFr4yxXpWO_6ORB0_2TnE5atDxQt2RoCNY8QAvD_BwE (accessed March 20, 2023). ↩︎

NA, "Mental Health Disparities: Diverse Populations", 2023, https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/diversity/education/mental-health-facts ↩︎

Mayo Clinic Staff, "Teens and social media use: What's the impact?", Mayo Clinic, Feb 26, 2022, https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/tween-and-teen-health/in-depth/teens-and-social-media-use/art-20474437 (accessed April 16, 2023). ↩︎

Mayo Clinic Staff, "Teens and social media use: What's the impact?", Feb 26, 2022,https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/tween-and-teen-health/in-depth/teens-and-social-media-use/art-20474437 ↩︎

Jon Haidt, "Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic in Teen Girls. Here’s the Evidence.", After Babel, Feb 22, 2023, https://jonathanhaidt.substack.com/p/social-media-mental-illness-epidemic (accessed March 5, 2023). ↩︎

NA, "Best Practice Highlights for Treating Diverse Patient Populations", American Psychiatric Association, 2023, https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/diversity/education/best-practice-highlights (accessed April 23, 2023). ↩︎

NA, "Supporting diverse communities",* American Foundation for Suicide Prevention*, 2023, https://afsp.org/supporting-diverse-communities?gad=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwrpOiBhBVEiwA_473dOLYcdx1nZgf1F2LquOO7GfaG8Ux98rseAtTeOZIRSu9dDKHaab35xoCmWAQAvD_BwE (accessed April 23, 2023). ↩︎

NA, "Five tips to maintain your mental health while using social media", UNICEF, Feb 8, 2021, https://www.unicef.org/romania/stories/five-tips-maintain-your-mental-health-while-using-social-media (accessed April 23, 2023). ↩︎

M. Clark and Debra Drewry, "Similarity and reciprocity in the friendships of elementary school children.", American Psychological Association, 1985, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1986-14209-001 (accessed April 30, 2023). ↩︎

Caroline Oppenheimer and Benjamin Hankin, "Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents: A Short-Term Multi-Wave Investigation of Longitudinal, Reciprocal Associations", National Library of Medicine, 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035302/ (accessed April 30, 2023). ↩︎

Dante Cicchetti and Karen Schneider-Rosen, "Toward a transactional model of childhood depression.", American Psychological Association, 1984, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1985-17455-001 (accessed April 30, 2023). ↩︎

M. Kovacs, "Children’s Depression Inventory", American Psychological Association, 1978, https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft00788-000, W. Furman and D. Buhrmester, "Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks.", American Psychological Association, 1985, https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0012-1649.21.6.1016 (accessed April 30, 2023). ↩︎

Oppenheimer and Hankin, "Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents: A Short-Term Multi-Wave Investigation of Longitudinal, Reciprocal Associations", 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035302/#R23 ↩︎

Oppenheimer and Hankin, "Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents: A Short-Term Multi-Wave Investigation of Longitudinal, Reciprocal Associations", 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035302/#R23 ↩︎

Oppenheimer and Hankin, "Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents: A Short-Term Multi-Wave Investigation of Longitudinal, Reciprocal Associations", 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035302/#R23 ↩︎

Oppenheimer and Hankin, "Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents: A Short-Term Multi-Wave Investigation of Longitudinal, Reciprocal Associations", 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035302/#R23 ↩︎

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035302/table/T1/?report=objectonly ↩︎

Oppenheimer and Hankin, "Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents: A Short-Term Multi-Wave Investigation of Longitudinal, Reciprocal Associations", 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035302/#R23 ↩︎

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/core/lw/2.0/html/tileshop_pmc/tileshop_pmc_inline.html?title=Click on image to zoom&p=PMC3&id=4035302_nihms581009f1.jpg. ↩︎

Oppenheimer and Hankin, "Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents: A Short-Term Multi-Wave Investigation of Longitudinal, Reciprocal Associations", 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035302/#R23 ↩︎

NA, "Promoting Healthy Relationships in Adolescents", The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Oct 24, 2018, https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/11/promoting-healthy-relationships-in-adolescents (accessed May 1, 2023). ↩︎

Jazmin Reyes-Portillo, "About Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Adolescents (IPT-A)", Columbia University Department of Psychiatry Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2023, https://childadolescentpsych.cumc.columbia.edu/articles/interpersonal-therapy-adolescents-ipta (accessed May 1, 2023). ↩︎

NA, "The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of adolescents and youth", UNICEF, 2020, https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/impact-covid-19-mental-health-adolescents-and-youth (accessed May 1, 2023). ↩︎

NA, "New CDC data illuminate youth mental health threats during the COVID-19 pandemic", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 31, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/p0331-youth-mental-health-covid-19.html#:~:text=According to the new data,hopeless during the past year (accessed May 1, 2023). ↩︎

Nicola Fazio et al., "Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 Pandemic Period in the European Population: An Institutional Challenge", National Library of Medicine, Aug 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9367746/#app1-ijerph-19-09347 (accessed May 1, 2023). ↩︎

Nicola Fazio et al., "Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 Pandemic Period in the European Population: An Institutional Challenge", Aug 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9367746/#app1-ijerph-19-09347 ↩︎

Arielle Baskin-Sommers et al., "Adolescent civic engagement: Lessons from Black Lives Matter", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Oct 4, 2021, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2109860118 (accessed May 3, 2023). ↩︎

Arielle Baskin-Sommers et al., "Adolescent civic engagement: Lessons from Black Lives Matter", Oct 4, 2021,https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2109860118 ↩︎

Rachel Jenkins et al., "Social, economic, human rights and political challenges to global mental health", National Library of Medicine, Jun 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178190/ (accessed May 3, 2023). ↩︎

Rachel Jenkins et al., "Social, economic, human rights and political challenges to global mental health", Jun 2011,https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178190/ ↩︎

NA, "World Mental Health Day 2022",* World Health Organization*, 2022, https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-mental-health-day/2022 (accessed May 3, 2023). ↩︎